This conversation will be determinant for the selection of residents. Éric explains that “there isn’t a scientific method for this selection. The key element in the decision is trying to understand and perceive whether there is a genuine interest in breaking the cycle of crime, for whatever reason. There must be a willingness to change the paradigm, to not repeat an offence.” In any case, the final decision will be up to the penalty enforcement judge, who is responsible for determining that the inmate will serve the final phase of his sentence under a regime of placement outside a prison facility.

Usually, the period of residence on the homestead extends from the 6 months to 1 year preceding the release. Although some exceptions may be made to this rule, residents shall be 25 years or older. In fact, since sentences tend to be long, the final phase of their execution usually occurs beyond young age.

FINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY MODEL

The project’s financial sustainability is guaranteed by revenue coming from different sources. La Ferme de Moyembrie receives from the prison administration a daily amount of €35.00 per resident. This value is three times lower than the cost that the same resident would represent if incarcerated in the common prison system. About 25% of the project’s budget is covered by the resources of the homestead, namely by the sale of produced products. In addition to these amounts, the salary due to residents, by virtue of their “social insertion contracts”, is paid by the Ministry of Labour and Social Security. A portion of that salary is withheld to pay a pension to La Ferme de Moyembrie, as contribution for the residents’ accommodation and food costs.

The project also receives public funding, namely grants for the prevention of delinquency and for social cohesion. The use of patronage or private financing is used only for material and concrete projects, such as the improvement of buildings and machinery used in the work of the estate.

“We are asked how we are planning to grow”, says Éric. And he adds: “We don’t want to grow, at least not in terms of numbers in this homestead. The secret of this project’s success also relies on our small dimension, which allows us to keep a close relationship with each one of the 20 residents”.

The secret of this project’s success also relies on our small dimension, which allows us to keep a close relationship with each one of the 20 resident

SAFETY GUARANTEES

This placement à l’extérieur manages, not only matters regarding logistics and spaces, but also the residents’ routines and security. There are no prison guards in the homestead. This is perhaps the most representative indicator of one of the key elements to the success of this project: the principle of trust in the residents. The experience of being trusted can be transformative in any circumstance, but this transformative potential is enhanced when there is a risk or a space to let down.

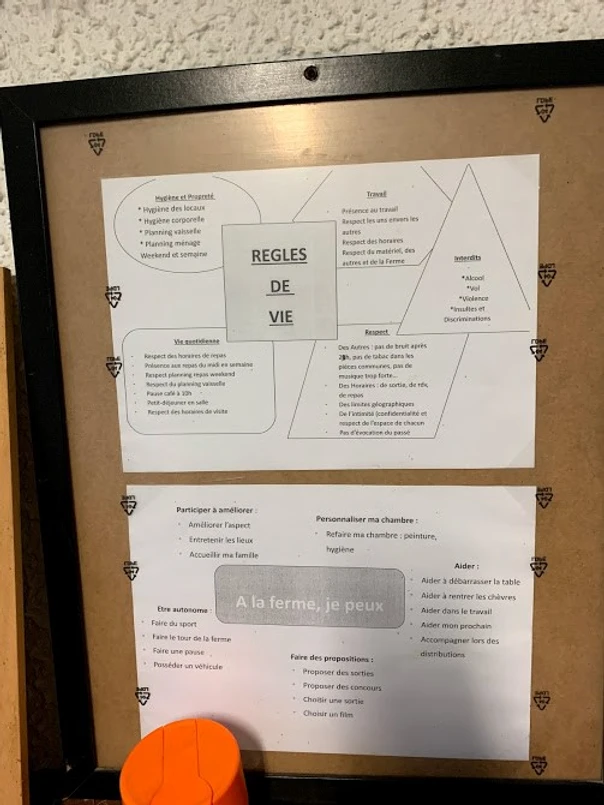

The absence of prison guards and of a permanent control of residents, either by caution or by default, holds them accountable. Éric says that, over the years, he witnessed miracles of transformation at La Ferme de Moyembrie triggered by this attitude of trust that residents are not used to in the common prison system. “Especially because they come from an environment of distrust between them, distrust of themselves, distrust of the justice system”, explains the co-president. Trust is also in the small details: each resident’s room, which must be clean and organised according to the house’s rules of life, is also a private area per excellence and, for this reason, it is never visited, except by invitation.

During the 24 hours of the 7 days of the week, there is always in the homestead a representative of La Ferme de Moyembrie, either a volunteer or an employee, who the residents can call if needed. As a rule, and under the law, the residents’ leaves must be authorised by a judge. In practical terms, those who are in charge of La Ferme de Moyembrie (be it the co-presidents or the supervisors) have delegated powers to authorise, in writing, leaves related to health matters, employment or reintegration.

Despite the absence of prison guards, there are points of contact between La Ferme de Moyembrie and the common prison system. The homestead is visited every two weeks, by a representative of the Reintegration Council of the nearby prison facility, where a good half of the residents were serving sentence before being admitted to La Ferme de Moyembrie. In such regular visits, individual talks with each resident take place, in order to evaluate their situation and to establish a connection between them and the court, if needed.

Security is also based on a clear definition of the fundamental rules for the proper functioning of the homestead. The violation of these rules necessarily implies consequences, which, depending on the gravity of the situation, can range from a formal warning by the court to a return to the common prison system.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE COMMUNITY

The relationship with the enlarged community started to be worked on from the first moment, by Jacque and Geneviève, who were an esteemed couple in the community and maintained a close relationship with the local authorities. The founders had an early sensitivity that still remains today in Moyembrie: that, although a real reintegration of ex-offenders requires the involvement of society, there are fears in local communities that cannot be underestimated, namely regarding the risk which is commonly associated with interaction with people who, at some point in their life, committed a crime. In order to avoid a counterproductive social alarm, these fears from the communities should not be disregarded, but rather deconstructed daily, through personal knowledge of concrete stories.

Nowadays, explains Éric, residents give life to the local economic activities, not only for the goods they produce but also for the services they consume locally and for they make themselves known, approaching the community and deconstructing negative myths that tend to be associated with prisoners and ex-prisoners.

The community’s involvement is even reflected by the local Maire (Mayor) – who is an ex officio member (‘membre de droit’) of the association’s board of directors – and by his wife, a volunteer in the kitchen of La Ferme de Moyembrie. The preparation of the residents’ future also covers their personal relationships, either within the family or friendship circles. On average, 70% of residents receive visits on weekends or visit their loved ones during permitted leaves.

THE IMPACT OF THE PROJECT

La Ferme de Moyembrie receives annually around 50 residents, responding to just 1/3 of the 150 requests for admission that the project receives. Since 2000, more than 500 people have benefited from this project. Each resident stays on the homestead for an average of 9 months, a time that must be delimited and is considered sufficient to intermediate a life in freedom: La Ferme de Moyembrie must serve as a springboard for an exit that is desired to happen. All residents have a housing solution once they leave the homestead and, in the three subsequent months, 60% of the ex‑residents find a life orientation or occupation, whether it is a job, training, retirement or integration in an Emmaus community.

La Ferme de Moyembrie also impacts the lives of 40 volunteers and 9 employees, hired not only to supervise agricultural or technical activities (such as farming, cheese production, livestock and maintenance of vehicles), but also to manage the daily life of the farm: these workers provide social support for residents, develop partnerships and make part of the decisions to welcome or exclude a resident.

Generally, in France, the recidivism rate between ex‑inmates who served part of their sentence in a ‘placement à l’extérieur’ is lower than the one verified amongst ex-inmates who entirely served their sentence in the common prison system. That being said, the impact of La Ferme de Moyembrie on recidivism isn’t easy to measure because some former residents gradually lose contact with the homestead. Éric explains that this lack of contact is often a good sign. “There is a cycle that comes to closure in their lives – that of serving a sentence – and a new cycle that is generated, that regenerates them.” La Ferme de Moyembrie, despite being a ‘placement à l’extérieur’, is still where they served a sentence and, to that extent, is associated with an old cycle. On the other hand, there are former residents who, by their own choice, keep in touch with the homestead and do so as a form of gratitude, essentially to share with Éric and the other employees of La Ferme de Moyembrie the progress they have achieved.

A HOMESTEAD LIKE AN AIRPORT

La Ferme de Moyembrie is a transformed project. It started by being a shelter for people excluded from society and it was transformed into a house for ex‑prisoners, to be, nowadays, a transition house before and towards freedom. At the time of its foundation, it did not aspire to be what it is today. It became what it had to be, as it responded to the needs felt. And it did so, says Éric, through a solid and committed team of “people who, much more than being competent for the work they do there, deeply identify with the values of La Ferme de Moyembrie” and make a choice for simplicity in living together with residents. The governance of the project is shared amongst all, in a horizontal and not vertical logic. In the words of Simon, one of the supervisors hired at La Ferme de Moyembrie, “on the farm, we try to make all decisions within the team, collectively, and also make as many decisions as possible together with the residents”.

It is a transformed project that transforms lives both inside and outside. Upon their arrival at the homestead, residents are accompanied to a general medical visit, where an individualised health plan is designed. The La Ferme de Moyembrie takes care of the residents’ image because it believes that the outside triggers the most important inner work of self-esteem and awareness of our intrinsic dignity.

And lives are transformed gradually. “While imprisoned, these men dream of what they will be able to do after release. The period in the homestead, more than a timefor dreaming is a time for readjustment”, explains Éric. The 9-month period at La Ferme de Moyembrie shall be an opportunity to relearn the reality, to normalise routines and to reconnect with the self and personal ties.

One of the residents, in his testimony, says that when he got out of prison he was really lost. “I no longer knew what money was. To buy a laptop, I gave the employee my wallet and said, “Help yourself”. I didn’t understand anything and was lost. Now I am ready to get out and capable of trusting.” In Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique, there is a homestead that might be compared to an airport since it is an intermediate place for freedom.

Life’s a train. When we leave a train, he doesn’t wait for us. We can’t release prisoners from prison with their belongings inside a bin bag and say: “That’s it, you’re free”. Is that freedom? Without money, without anything? No. The passage through the homestead, for one year, with time and support for us to rebuild ourselves, that indeed, is the beginning of freedom.”

Philippe’s Testimony (ex-resident), available at www.fermedemoyembrie.fr

institutional changes would have to happen. First, mass incarceration would need to come to an end and more money needs to be put in alternatives to prison. This would decrease the population in prisons meaning that down-sizing would be more tangible. Second is cultural change. RESCALED works because people believe that prisoners deserve better treatment and that they are human. The prison system in the US is deeply rooted in racism and cultural misconceptions of crime and punishment.

institutional changes would have to happen. First, mass incarceration would need to come to an end and more money needs to be put in alternatives to prison. This would decrease the population in prisons meaning that down-sizing would be more tangible. Second is cultural change. RESCALED works because people believe that prisoners deserve better treatment and that they are human. The prison system in the US is deeply rooted in racism and cultural misconceptions of crime and punishment.