In Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique, about a two-hour drive from the heart of Paris, there is a homestead that may be compared to an airport.

In 1990, a couple of retired agriculture engineers, Jacques and Geneviève Pluvinage, decided to invest their life savings in the purchase of a 24-hectare plot, planning to work and live there, welcoming people excluded from society that had nowhere else to live. Jacques, who was also a visitor in a local prison, began to receive letters from inmates that were about to be released, but without any support and without knowing where to go. Jacques and Geneviève were willing to welcome in their homestead these people, with whom they shared family life, the fieldwork, and all the incomes from production. Thus, the way was paved for “La Ferme de Moyembrie”, a place that still exists today, with an ever more enlightened and delimited vocation.

In the early 2000’s, a penalty enforcement judge discovered the homestead and launched the challenge for “La Ferme de Moyembrie” to start welcoming sentenced persons who were not yet released, but who were serving time under a regime of placement outside a prison facility (‘placement à l’extérieur’ or work release).

In 2004, the first agreements were formally signed with the Reintegration Prison Services that gave La Ferme de Moyembrie the statute of a “placement à l’extérieur”, making it possible for the homestead to accommodate detainees, in order to prepare them for release.

WORK AND LIVE IN LA FERME DE MOYEMBRIE

La Ferme de Moyembrie still exists today, with the same vocation and is co-directed by Jean-Claude Simon and Éric de Villeroché, who generously welcomes all those who want to get familiarised with the work developed in the homestead, while emphasising that a “one-day visit will always fall below an in-depth knowledge of the true essence of that place”.

La Ferme de Moyembrie reckons that work plays a structural role in reintegration. The residents work and live in the homestead. Éric says that, from the foundation of the project, the invitation for the inmates is “you come, you live and work here, we work and live together, in a worthy and useful job and we live from that same work, from what we produce”.

You come, you live and work here, we work and live together, in a worthy and useful job and we live from that same work, from what we produce.

All residents work in activities in the homestead which can be related to agriculture, the rearing of goats and laying hens, the production of cheese and yogurt, cooking and the construction or maintenance of machines and vehicles. Each resident celebrates, to that effect, a social insertion contract that predicts 20 hours of weekly work.

Special skills and abilities aren’t required, but the approach to work is professional and the economic challenges are real: La Ferme de Moyembrie is a certified homestead in organic agriculture that compromised itself to provide 140 vegetable baskets per weak, during the entire year. The professional work educates for responsibility and gives back structure and organisation to the everyday life of the residents. Éric explains that organic agriculture has two special variants: the evidence of fruitful rewards in the production – enhancing a sense of pride for the achieved results – and the act of “taking care of the earth and the animals, which is an invitation to take care of life, the self and the others”.

The residents work in the farm and live in a house therein. Each resident has a key for their individual room, where they can receive visits and restore intimacy bonds. Only this way the residents can regain the privacy that was taken from them during imprisonment. “The first night of the residents is always tumultuous, many of them can’t sleep”, says Éric. “And notice, we are in a calm and silent village. These people were deprived of their own space for so long that they don’t know how to deal with silence and with a safety and privacy environment anymore”

The daily routine seeks to be as similar as possible with the reality after release. The breakfast is served in the common meals room. The work journey starts at 8am and ends by 12am, with a brief pause for coffee in the middle of the morning. At 12:15am the lunch is served and necessarily shared. After lunch, there’s a free schedule so the residents relearn to manage their own time. All of them are encouraged to move forward on priority issues and are supported in their efforts. Some, if they wish so, attend driving lessons, courses or specific trainings – such as creative writing or relaxation – others have the initiative to suggest recreational activities within the community or take advantage of this time to start restoring ties with their loved ones, to regularise their administrative situation or to legalise their residence. The community dinner is served at 7pm, but residents can choose to dine on their own. Some activities, with voluntary adhesion, also occur at night and may consist of a simple shopping trip or of badminton and football trainings at local sports associations, on a weekly basis.

Family and friends’ visits take place on weekends from 9am to 7pm. Community life in the homestead, just like any other, isn’t always easy. There is a relearning to be done at this level as well. For this reason, every Monday afternoon there is a pivotal moment of reflection in plenary, where the previous week is evaluated and the following week is projected. During that time, responsibilities for house dynamics are also divided and shifts are defined to help prepare meals and clean common areas.

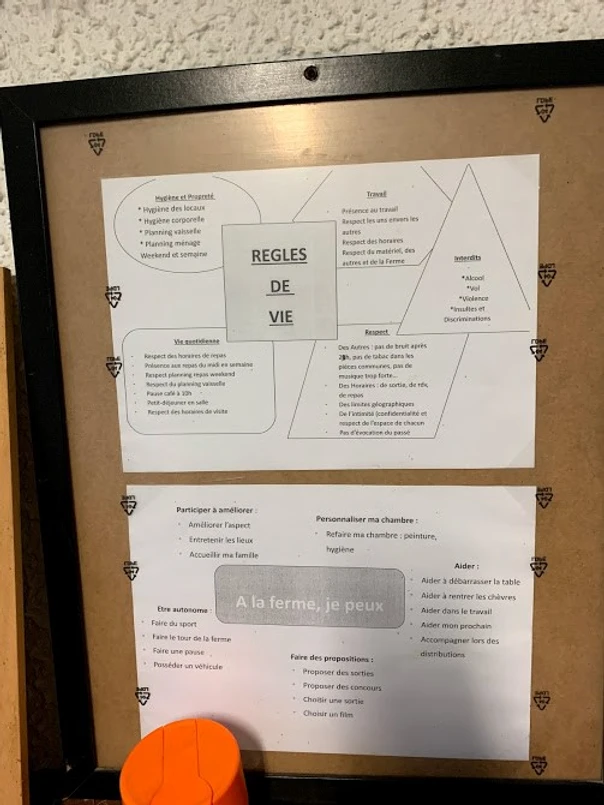

At the core of the success of this project are the life rules that are clearly displayed and explained to residents and relate to hygiene (personal and spatial), work, daily life, prohibited consumptions and mutual respect. The latter is an inviolable principle at La Ferme de Moyembrie, where no physical violence is allowed and where it is expressly “forbidden to evoke the past” as a weapon of verbal violence. It is even a rule of the homestead that residents do not reveal the crime they have committed, as a means to prevent the perpetuation between them of hierarchies which, in the common system, tend to be established on the basis of the crime committed.

At the core of the success of this project are the life rules that are clearly displayed and explained to residents and relate to hygiene (personal and spatial), work, daily life, prohibited consumptions and mutual respect. The latter is an inviolable principle at La Ferme de Moyembrie, where no physical violence is allowed and where it is expressly “forbidden to evoke the past” as a weapon of verbal violence. It is even a rule of the homestead that residents do not reveal the crime they have committed, as a means to prevent the perpetuation between them of hierarchies which, in the common system, tend to be established on the basis of the crime committed.

SELECTING THE RESIDENTS

When questioned about the process of selecting the residents, Éric starts by clarifying a point that he finds less expectable: the crime committed by an inmate is irrelevant, as are the skills that he may have acquired in the past to carry out the works developed on the homestead.

This project, as it exists today, was born from letters that, in 1990, inmates would write to the founder of the homestead. Thirty years later, this tradition continues. The access to La Ferme de Moyembrie is voluntary: any inmate can write to the homestead, asking to live there. After a first visit by a volunteer of the project to the inmate’s prison facilities, the candidate visits La Ferme de Moyembrie for a day, contacting for the first time with the reality of the homestead and having the opportunity to talk individually with all the supervisors present in the homestead that day, which range from 4 to 8 and may include Éric or Jean-Claude.

This conversation will be determinant for the selection of residents. Éric explains that “there isn’t a scientific method for this selection. The key element in the decision is trying to understand and perceive whether there is a genuine interest in breaking the cycle of crime, for whatever reason. There must be a willingness to change the paradigm, to not repeat an offence.” In any case, the final decision will be up to the penalty enforcement judge, who is responsible for determining that the inmate will serve the final phase of his sentence under a regime of placement outside a prison facility.

Usually, the period of residence on the homestead extends from the 6 months to 1 year preceding the release. Although some exceptions may be made to this rule, residents shall be 25 years or older. In fact, since sentences tend to be long, the final phase of their execution usually occurs beyond young age.

FINANCIAL SUSTAINABILITY MODEL

The project’s financial sustainability is guaranteed by revenue coming from different sources. La Ferme de Moyembrie receives from the prison administration a daily amount of €35.00 per resident. This value is three times lower than the cost that the same resident would represent if incarcerated in the common prison system. About 25% of the project’s budget is covered by the resources of the homestead, namely by the sale of produced products. In addition to these amounts, the salary due to residents, by virtue of their “social insertion contracts”, is paid by the Ministry of Labour and Social Security. A portion of that salary is withheld to pay a pension to La Ferme de Moyembrie, as contribution for the residents’ accommodation and food costs.

The project also receives public funding, namely grants for the prevention of delinquency and for social cohesion. The use of patronage or private financing is used only for material and concrete projects, such as the improvement of buildings and machinery used in the work of the estate.

“We are asked how we are planning to grow”, says Éric. And he adds: “We don’t want to grow, at least not in terms of numbers in this homestead. The secret of this project’s success also relies on our small dimension, which allows us to keep a close relationship with each one of the 20 residents”.

The secret of this project’s success also relies on our small dimension, which allows us to keep a close relationship with each one of the 20 resident

SAFETY GUARANTEES

This placement à l’extérieur manages, not only matters regarding logistics and spaces, but also the residents’ routines and security. There are no prison guards in the homestead. This is perhaps the most representative indicator of one of the key elements to the success of this project: the principle of trust in the residents. The experience of being trusted can be transformative in any circumstance, but this transformative potential is enhanced when there is a risk or a space to let down.

The absence of prison guards and of a permanent control of residents, either by caution or by default, holds them accountable. Éric says that, over the years, he witnessed miracles of transformation at La Ferme de Moyembrie triggered by this attitude of trust that residents are not used to in the common prison system. “Especially because they come from an environment of distrust between them, distrust of themselves, distrust of the justice system”, explains the co-president. Trust is also in the small details: each resident’s room, which must be clean and organised according to the house’s rules of life, is also a private area per excellence and, for this reason, it is never visited, except by invitation.

During the 24 hours of the 7 days of the week, there is always in the homestead a representative of La Ferme de Moyembrie, either a volunteer or an employee, who the residents can call if needed. As a rule, and under the law, the residents’ leaves must be authorised by a judge. In practical terms, those who are in charge of La Ferme de Moyembrie (be it the co-presidents or the supervisors) have delegated powers to authorise, in writing, leaves related to health matters, employment or reintegration.

Despite the absence of prison guards, there are points of contact between La Ferme de Moyembrie and the common prison system. The homestead is visited every two weeks, by a representative of the Reintegration Council of the nearby prison facility, where a good half of the residents were serving sentence before being admitted to La Ferme de Moyembrie. In such regular visits, individual talks with each resident take place, in order to evaluate their situation and to establish a connection between them and the court, if needed.

Security is also based on a clear definition of the fundamental rules for the proper functioning of the homestead. The violation of these rules necessarily implies consequences, which, depending on the gravity of the situation, can range from a formal warning by the court to a return to the common prison system.

RELATIONSHIP WITH THE COMMUNITY

The relationship with the enlarged community started to be worked on from the first moment, by Jacque and Geneviève, who were an esteemed couple in the community and maintained a close relationship with the local authorities. The founders had an early sensitivity that still remains today in Moyembrie: that, although a real reintegration of ex-offenders requires the involvement of society, there are fears in local communities that cannot be underestimated, namely regarding the risk which is commonly associated with interaction with people who, at some point in their life, committed a crime. In order to avoid a counterproductive social alarm, these fears from the communities should not be disregarded, but rather deconstructed daily, through personal knowledge of concrete stories.

Nowadays, explains Éric, residents give life to the local economic activities, not only for the goods they produce but also for the services they consume locally and for they make themselves known, approaching the community and deconstructing negative myths that tend to be associated with prisoners and ex-prisoners.

The community’s involvement is even reflected by the local Maire (Mayor) – who is an ex officio member (‘membre de droit’) of the association’s board of directors – and by his wife, a volunteer in the kitchen of La Ferme de Moyembrie. The preparation of the residents’ future also covers their personal relationships, either within the family or friendship circles. On average, 70% of residents receive visits on weekends or visit their loved ones during permitted leaves.

THE IMPACT OF THE PROJECT

La Ferme de Moyembrie receives annually around 50 residents, responding to just 1/3 of the 150 requests for admission that the project receives. Since 2000, more than 500 people have benefited from this project. Each resident stays on the homestead for an average of 9 months, a time that must be delimited and is considered sufficient to intermediate a life in freedom: La Ferme de Moyembrie must serve as a springboard for an exit that is desired to happen. All residents have a housing solution once they leave the homestead and, in the three subsequent months, 60% of the ex‑residents find a life orientation or occupation, whether it is a job, training, retirement or integration in an Emmaus community.

La Ferme de Moyembrie also impacts the lives of 40 volunteers and 9 employees, hired not only to supervise agricultural or technical activities (such as farming, cheese production, livestock and maintenance of vehicles), but also to manage the daily life of the farm: these workers provide social support for residents, develop partnerships and make part of the decisions to welcome or exclude a resident.

Generally, in France, the recidivism rate between ex‑inmates who served part of their sentence in a ‘placement à l’extérieur’ is lower than the one verified amongst ex-inmates who entirely served their sentence in the common prison system. That being said, the impact of La Ferme de Moyembrie on recidivism isn’t easy to measure because some former residents gradually lose contact with the homestead. Éric explains that this lack of contact is often a good sign. “There is a cycle that comes to closure in their lives – that of serving a sentence – and a new cycle that is generated, that regenerates them.” La Ferme de Moyembrie, despite being a ‘placement à l’extérieur’, is still where they served a sentence and, to that extent, is associated with an old cycle. On the other hand, there are former residents who, by their own choice, keep in touch with the homestead and do so as a form of gratitude, essentially to share with Éric and the other employees of La Ferme de Moyembrie the progress they have achieved.

A HOMESTEAD LIKE AN AIRPORT

La Ferme de Moyembrie is a transformed project. It started by being a shelter for people excluded from society and it was transformed into a house for ex‑prisoners, to be, nowadays, a transition house before and towards freedom. At the time of its foundation, it did not aspire to be what it is today. It became what it had to be, as it responded to the needs felt. And it did so, says Éric, through a solid and committed team of “people who, much more than being competent for the work they do there, deeply identify with the values of La Ferme de Moyembrie” and make a choice for simplicity in living together with residents. The governance of the project is shared amongst all, in a horizontal and not vertical logic. In the words of Simon, one of the supervisors hired at La Ferme de Moyembrie, “on the farm, we try to make all decisions within the team, collectively, and also make as many decisions as possible together with the residents”.

It is a transformed project that transforms lives both inside and outside. Upon their arrival at the homestead, residents are accompanied to a general medical visit, where an individualised health plan is designed. The La Ferme de Moyembrie takes care of the residents’ image because it believes that the outside triggers the most important inner work of self-esteem and awareness of our intrinsic dignity.

And lives are transformed gradually. “While imprisoned, these men dream of what they will be able to do after release. The period in the homestead, more than a timefor dreaming is a time for readjustment”, explains Éric. The 9-month period at La Ferme de Moyembrie shall be an opportunity to relearn the reality, to normalise routines and to reconnect with the self and personal ties.

One of the residents, in his testimony, says that when he got out of prison he was really lost. “I no longer knew what money was. To buy a laptop, I gave the employee my wallet and said, “Help yourself”. I didn’t understand anything and was lost. Now I am ready to get out and capable of trusting.” In Coucy-le-Château-Auffrique, there is a homestead that might be compared to an airport since it is an intermediate place for freedom.

Life’s a train. When we leave a train, he doesn’t wait for us. We can’t release prisoners from prison with their belongings inside a bin bag and say: “That’s it, you’re free”. Is that freedom? Without money, without anything? No. The passage through the homestead, for one year, with time and support for us to rebuild ourselves, that indeed, is the beginning of freedom.”

Philippe’s Testimony (ex-resident), available at www.fermedemoyembrie.fr

With the support of: