When a judge imposes a prison sentence, it has far-reaching consequences for the convicted person, for his or her family and the children involved. The consequences for children are often dire. For example, research warns that incarceration of a parent can disrupt children’s psychological and emotional development processes resulting in, for example, low self-esteem, anxiety, depression and attachment problems.

While these problems can arise from the absence of a mother and father, international research shows that women in detention are often responsible for the main caregiving responsibilities. When incarcerated, their children cannot always call upon the social network of the parent and there is no or little possibility for successful bonding with a parent. In Belgian prisons, children under the age of three can therefore stay in prison with their mothers. Several prisons provide specific facilities for mothers with children. Mothers and children can make use of specific support on the wing and ‘child friendly’ facilities. For example, working mothers can use the prison’s childcare facilities and are supported by services that are also provided in free society such as ‘Kind en Gezin’ (child and family).

While the presence of children in prisons is a daily reality, it remains an under-researched topic in Belgium and abroad. This lack of attention from politicians, scientists and media results in an institutional invisibility of these children (Pösö et al., 2010). As a result, the effects of incarceration on mother and child remain underreported and political pressure to address this situation remains limited. Nevertheless, the need is high: children are not punished however they live in the same context as persons who are subjected to the most severe punishment known today within the Belgian and European criminal justice system: imprisonment. In international literature such a stay in prison leads to a lot of complex debates that are situated at the intersection of different themes such as parental rights, children‘s rights, duties of parents and legal restrictions on imprisoned parents that make it difficult or impossible for them to take on certain responsibilities. This blogpost does not offer answers to all of these complex questions. We limit ourselves to the matter on how to ensure the rights of children and parents as much as possible in a society that permits the deprivation of mothers’ liberty. We moreover focus on the increasing political awareness on finding solutions.

THE CURRENT BELGIAN SYSTEM FALLS SHORT FOR MOTHERS AND THEIR CHILDREN IN DETENTION

Despite all efforts, we see that it is difficult to respect children’s rights in prison. This is partly because the systemic structures of today’s prisons do not sufficiently allow for the creation of a child-friendly environment. After all, in a prison there is institutional violence that interacts in subtle ways with all incarcerated persons. Despite the fact that children are not subject to punishment, their mere presence in this context makes them subject to control. Indeed, people in detention acquire certain codes and behaviour that allow them to survive in a highly controlled environment. Children even begin to normalize this control and adapt their behaviour. Striking examples from research describe, for example, how children re-enact situations in which they constantly count how many people are locked up in the cells (Tabbush & Gentile, 2013). In a Belgian study, a mother expressed her concern that her daughter imitates her and stands with her arms and legs spread as the mother does during a body search (Nuytiens & Jehaes, 2020). Clearly, children get used to institutional forms of control that are far removed from the context in which we want to see children grow up and flourish.

Women do not experience prison as a place where they can adequately perform their caregiving duties as mothers. Often, incarceration is accompanied by feelings of guilt and concerns about the impact of incarceration on parenting. Mothers feel they have failed as a parent because their child(ren) live(s) within the strict routine of prisons. The prison routine does not allow to respect their child’s rhythm. In Belgian research, mothers refer very specifically to the many hours they spend with their child in the limited space of the cell. This limited exercise space hinders children from getting rid of their energy. In addition, mothers feel ashamed about their daily humiliations, exposed to their children (Nuytiens & Jehaes, 2020).

While the context limits ways to perform a mother role, it remains important to encourage mothers to take on their parental duties. Not only for the mothers and children in question but also for our broader society. Studies on the desistance process from crime show that parenting can play an important role. Desistance refers to the gradual process by which people eventually stop committing crime. During this process, changes in perceptions of identity play a central role. In a variety of studies, individuals testify that taking on a father or mother role can change the perceptions of one’s identity in a positive way. One then no longer sees oneself as a delinquent but primarily as a father or mother.

It is therefore in the interest of the child, the mother and society at large to create an optimal parenting context.

A CRITICAL NOTE

Before we elaborate on ways to improve conditions for mothers with children, we wish to stress that this remains a pragmatic solution for countries that allow the imprisonment of parents. In our opinion, we should use detention houses only as an ultimum remedium and within a reductionist detention policy. Thus, a detention house for women should never legitimize the all too easy imprisonment of mothers with their children. This is in line with the view of the Council of Europe. It recommends that prior to sentencing, consideration should always be given to whether there is an alternative to detention for the parent, especially when it comes to a parent taking primary care of the child.

Thus, improvements to detention conditions should not prevent larger discussions on whether societies should abolish the incarceration of parents. Since it is still allowed in Belgium to imprison parents, the implementation of the proposal below should, in our opinion, go hand in hand with a system that takes a critical look at any deprivation of liberty. Below we describe models that allow to limit detention harm, but we wish to emphasize that any form of deprivation of liberty causes harm.

WHAT DO WE LEARN FROM ABROAD?

While Belgian politicians only recently started to search for ways to starkly improve the situation for mothers in detention, other countries have more experience with specific detention modalities for mothers. Before we elaborate on the proposals that came to the forefront in Belgium, we take a look at the situation in Spain, a country with a longer history on detention modalities for mothers with children. To our knowledge, Spain is one of the few countries in Europe that pays specific attention to small-scale and community integrated prison modalities for mothers with children.

In Spain, article 38.2 General Penitentiary Organic Law (LOGP) regulates the presence of minor children inside prisons. Women who are imprisoned can keep their young children with them. Since the 1980s, a series of structures were set up looking for optimal prison conditions. This is how the following four structures were put into operation:

— First, there are Mothers’ Units (or mothers’ modules) (Articles 17 and 178 -181 Real Decreto por el que se aprueba el Reglamento Penitenciario 190/1996, 9 February (RP)). These are specific modules inside closed prisons. The modules are, however, architecturally separated from the rest of the building. As a consequence, there is no interaction between children and other prisoners. Most of the children under the age of three who accompany their mothers during the sentence reside in these modules inside the prisons. Although these modules are defined as adapted to children’s needs, in reality, children do not have enough outdoor spaces or ample places to move freely. Additionally, children have to get used to the prison regulations, the rules of coexistence and schedules that regulate daily prison life.

– Second, there are Family Modules or Family Units. In these units, father and mother jointly share the raising of children, only in those cases in which both are serving a prison sentence in a closed prison.

— Third, there are Dependent Units or “halfway houses”. These are small homes for people that are categorised as posing a low security threat or that are eligible for the open regime[1]. These houses are generally managed by NGOs in cooperation with Penitentiary Institutions. Article 165 RP defines Dependent Units as “architecturally located units outside the prison grounds, preferably in ordinary dwellings in the community environment, without any sign of external distinction related to their dedication”. Although there is not much research on this issue and the law does not specify much more about the development of motherhood in these Units, it has been considered important to refer to an example of a Dependent Unit that houses mothers with their children in Spain, the case of the Dependent Unit associated to the Prison Alcalá de Guadaira (Seville, Andalusia). It is a Dependent Unit, managed by the “Nuevo Futuro” association since 1992, and consists of a home to house women who pose a low security threat and who have their children under three years of age with them (there are some cases in which they can house second level inmates, but this is of a more exceptional nature). As stated in the Defensor del Pueblo Report (2006): “It is a house, with capacity for eight women with their children, located in the urban centre of Seville. It consists of a central patio, three floors and a roof terrace; on the ground floor there is an office for the prison officer stationed there, a living room, a children’s playroom, kitchen, dining room and a toilet, on the 2nd and 3rd floor are the bedrooms and the rest of the rooms ” (p. 191). The organization of life within the home corresponds to the Association “Nuevo Futuro” and the regime of the women inmates mainly consists of domestic tasks, attention and care of children, etc. The inmates compliance with the schedules, behaviour and additional leaves are supervised by the Penitentiary´s Institution staff, but staff members do not wear a uniform. In addition, women can also be supported by the prison psychologist or social worker. The reality is that these Dependent Units are less and less used in Spain. Since third-level inmates who are women with children started to be housed, an attempt is being made to intensify the fully open third-level concession as well as the use of electronic monitoring to avoid transferring this type of inmates to these Dependent Units.

— Lastly, there are Mothers´ External Units. In 2004, the General Secretariat of Penitentiary Institutions decided to remove children from prisons. In order to achieve this goal, external units were built, away from the penitentiary centres with a vocation of integration in the community. These units are a “hybrid” model between the Dependent Units and the Mothers’ Units inside the prisons. These External Units depend on the so-called Social Insertion Centres (open prisons), and are located away from prisons that are usually located next to the Social Insertion Centres where women can live. These units can house:

- convicted women classified in ordinary regime who are in charge of children under three years of age;

- women in a situation of preventive detention (awaiting a final judicial sentence) with minor children in their care (under three years of age), only when authorized by the judge after an evaluation;

- exceptionally, these units house third-level inmates or inmates in open regime (however, these women usually go to dependent units);

- women who are pregnant for six months and who find themselves in circumstances described above

- exceptionally, children will be allowed to stay with their mothers until the age of six. After three years, it will be evaluated whether their presence in prison is a better alternative than being separated from the mother. Also, women assigned to the Unit with a child under three may request the admission of another child not older than six years.

In order to serve their sentence in Mothers´ External Units, women have to accept the acquisition of work, voluntary and active participation in the proposed therapeutic programs, maintaining healthy lifestyle and conduct in accordance with the rules and participation in a therapeutic program in the case she is or has been a drug user. Also, these units have “non-aggressive” surveillance based on electronic surveillance control systems composed of cameras, alarms and presence detectors. Obviously, children are not subject to any measure of legal restraint. The main objective for them is to enjoy childhood, having contact with the outside world and relating to their families and other children.

RESCALED BELGIUM AND DETENTION HOUSES FOR MOTHERS

It is clear that several European countries have been developing different forms of detention over the years in order to be able to respect children’s and parents’ rights. In Belgium, vzw De Huizen/RESCALED proposes the concept of detention houses for mothers and children. It is believed that this will improve their situation.

These detention houses, similar to the Dependent Units in Spain, are small-scale forms of deprivation of liberty that are integrated in society and allow for differentiation. In this way, we can minimize detention harm, develop an approach tailored to the women and children who reside there. Additionally, mothers can resume responsibilities and perform caring responsibilities. Moreover, proper guidance in taking up the mother role can promote the development of the bond between mother and child. Finally, the domestic atmosphere of the detention house allows children to live and grow at their pace.

This model suits most incarcerated mothers because, generally speaking, this group poses little to no escape risk. While a closed and highly secured prison cuts itself off from society, detention houses remain connected to the immediate environment thanks to their proximity and integration in the community. This facilitates visits from other children and family members or services and mothers. Moreover, children have the opportunity to maintain or re-establish social contacts and have access to services outside the house. This uninterrupted connection with the neighbourhood and the social anchoring of the detention house ensure the disappearance of an institutionalized living environment, allowing us to actually work on reintegration.

(Do you want to know more about the RESCALED-concept? www.rescaled.org / www.dehuizen.be )

POLITICAL SUPPORT

In Belgium, political support for this kind of detention houses is growing.

In September 2019, Belgium opened its first transition house. This house is similar to what is internationally known as a halfway house. In Belgium it is a house, integrated in the community, which accommodates imprisoned persons. Imprisoned persons within 18 months before their legal conditional release date can be transferred to a transition house. Consequently, this house is only open for people who find themselves in a specific part of their detention trajectory. Political awareness is growing that not only this specific group of people might benefit from small-scale detention. In 2020, this was emphasized by the new federal government’s coalition agreement. This agreement states that:

In cooperation with the communities, the federal government creates a framework to actively prepare the reintegration of prisoners from the start of their sentence through individual detention plans, the strengthening of psychosocial services, and the further development of small-scale detention projects for certain groups of prisoners (e.g. parents with children, detainees shortly before release, young offenders, etc.) (Federal Coalition agreement, 2020: 71).

The current debates in the Justice Commission of the Federal Parliament, show that the opening of new houses is high on the political agenda and several steps are being taken to open new houses in the near future (e.g. mayors have been contacted in order to find support for the opening of new houses and at the beginning of August, 19 communities showed their interest in a detention house). While the coalition agreement states that the detention houses should improve reintegration in society, an analysis of the debates in the parliament shows that this is also clearly linked to other goals such as the improvement of detention conditions.

In the Parliament, debates that focus on the incarceration of mothers in detention additionally provide insight into the broader policy for parents in detention that the Minister aims to develop. In January 2021, the Minister stressed his belief that detention houses will reduce recidivism. Besides the previously mentioned goals of detention houses (reintegration, improvement of detention conditions, expansionism), a reduction of recidivism is another goal that increasingly pops up. Moreover, and on a critical note, the interpretation of what reintegration means often appears to be reduced to the absence of recidivism. When questioned in regard to the opening of a detention house for children and mothers, the Minister clarifies this policy view:

The desire to focus on “parents with children” is related to the desire to reduce recidivism. After all, we know that maintaining family ties is an asset for effective reintegration. That said, it is still too early to determine exactly which groups will be considered for detention houses, since that will depend on several factors, such as the nature of the buildings chosen and their geographical location, but it will obviously be the intention to target specific groups of detainees, whom we will provide with an adapted framework and supervision, with a view to reducing recidivism. (Justice Commission, 21 January 2021: 11).

Later on, in May 2021, the Minister repeats his intention to open detention houses for people with a specific profile such as women with or without children. Concerning the specific group of women with children, he highlights that Belgian’s largest prison with 1190 places, that is currently being built, will have an external unit that is adapted to mothers with a child. In the future, the Minister generally hopes that detention houses will provide a better context for parents:

…In this regard, it is certainly possible to provide a transition house for women, with or without children. In addition, on the Haren prison site, outside the perimeter, there will be a number of small-scale units of which one is adapted to mother and child, and where detention conditions will be created that meet the same principles of small scale and porosity. Small-scale detention houses are an interesting addition to the existing capacity, but added value should not be limited to mothers only. There are few women who have a child with them during detention. Also for other parents a transition home or a detention house often provides added value, because contact can be made with children in a much more homely atmosphere (Justice Commission, 11 May 2021: 23).

Clearly, this policy entails some improvements to the current detention conditions of mothers in large prisons. However, it is also stressed that these houses are seen as an ‘addition to the existing capacity’ and are not considered as a replacement of prisons but are being opened to increase the country’s prison capacity. For decades now Belgium is facing serious prison overcrowding. At this moment the overcrowding rate is still one of the highest in Europe. National and international pressure currently results in expansionist policies rather than reduction in the use of imprisonment. Detention houses clearly play a role in this expansionist policy. The larger debates on the use of imprisonment that we hoped detention houses would provoke, are unfortunately absent. Another negative note is about the belief that an external unit of what will be the largest prison of Belgium can provide the same support as detention houses. However, we wish to stress that the units remain part of a larger entity that is located in a remote area.

FUTURE PERSPECTIVES

Nowadays we must not remain blind for the far-reaching and pernicious consequences of a stay in prison, especially when it comes to our children who are not undergoing punishment. We even dare hope that this awareness can also lead to broader adjustments, including for parents whose children are not staying with them in prison. After all, we hope to evolve towards an optimal parenting context for all children. Also for children with a parent in detention. For these reasons, we advise politicians to re-examine the incarceration of mothers and children; and of parents in general. The modalities in Spain, as discussed above, show that some countries pay special attention to this group in detention. Belgium cannot stay behind.

We believe that small scale and community integrated detention houses can be part of this solution. Moreover it is our opinion that this approach should be part of a wider debate on imprisonment and especially the imprisonment of parents and its impact on children. For us, a critical look at the imprisonment of parents (regardless of the place where detention takes place) is crucial and intrinsically connected to this debate.

Critical reflection on the current Belgian policy in relation to detention houses is necessary. We encourage all efforts to improve detention conditions focusing on detention houses to achieve this goal, but at the same time we are worried about the fact that this is embedded in an expansionist prison policy. We moreover recognize the need for a thorough discussion on the interpretation of reintegration, as a more complex process rather than a reduction of recidivism. Finally, we wish to stress that also detention houses can cause harm. We therefore believe that criminal justice interventions and criminal punishment should always be seen and used as ultimum remedium.

REFERENCES:

- Defensor del Pueblo Andaluz (2006). Mujeres privadas de libertad en centros penitenciarios de Andalucía. Informe al Parlamento. Defensor del Pueblo Andaluz.

- Martí, M. (2021). Prisoners in the community: the open prison model in Catalonia. Nordisk Tidsskrift for Kriminalvidenskab, 106(2), 211–231. doi:10.7146/ntfk.v106i2.124777

- Ministerio del Interior-Secretaría General de Instituciones Penitenciarias. Unidades externas de madres. Ministerio del Interior-Secretaría General Técnica.

- Navarro Villanueva, C. (2018). El encarcelamiento femenino. Barcelona: Atelier. Libros Jurídicos.

- Nuytiens, A. & Jehaes, E. (2020). When your child is your cellmate: The ‘maternal pains of imprisonment’ in a Belgian prison nursery. Criminology & Criminal Justice,

- Pösö, T. ; Enroos, R. & Vierula, T. (2010). Children Residing in Prison with their Parents. The Prison Journal, 90, 516-533.

- Real Decreto 190/1996, de 9 de febrero, por el que se aprueba el Reglamento Penitenciario.

- Tabbush, C. & Gentile, M.F. (2013). Emotions behind bars: The Regulation of Mothering in Argentine Jails. Journal of Women in Culture and Society, 39 (1), 131-149.

[1] “level three, similar to the English category D, corresponds to people who are serving prison terms under open conditions. Towards the end of their sentences, third-level prisoners may be released on parole” (Martí, 2019, p. 213).

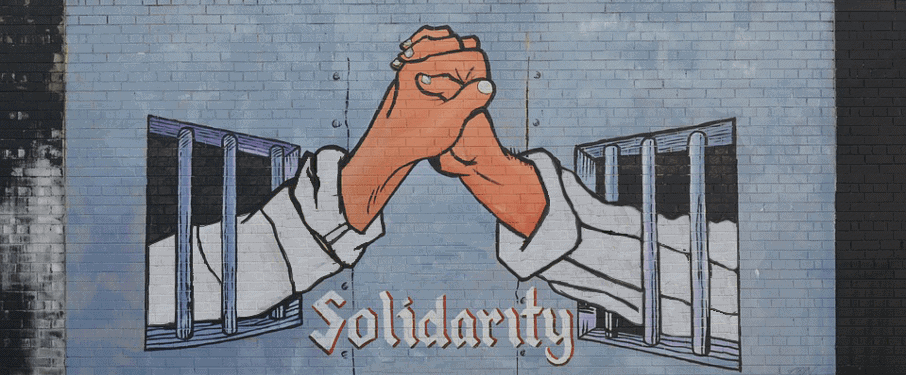

Photo of unknown author licensed by CC BY-ND

Lutterbach penitentiary center (in the Grand Est region, near Mulhouse),

Lutterbach penitentiary center (in the Grand Est region, near Mulhouse),